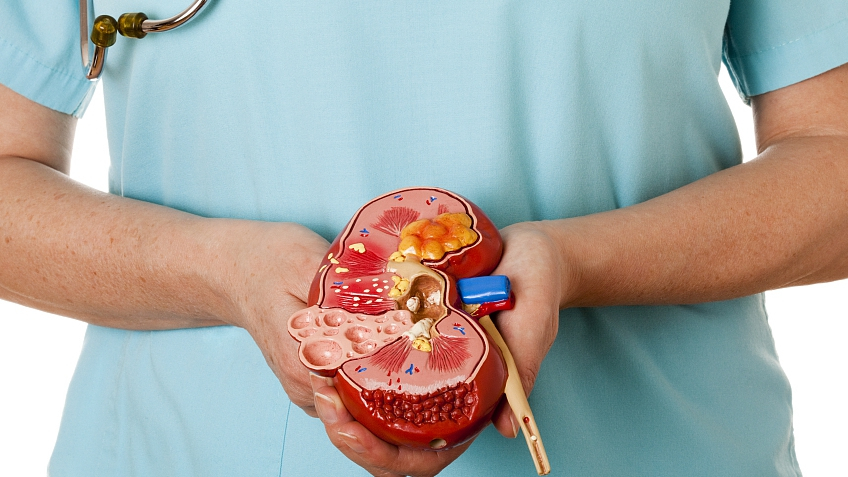

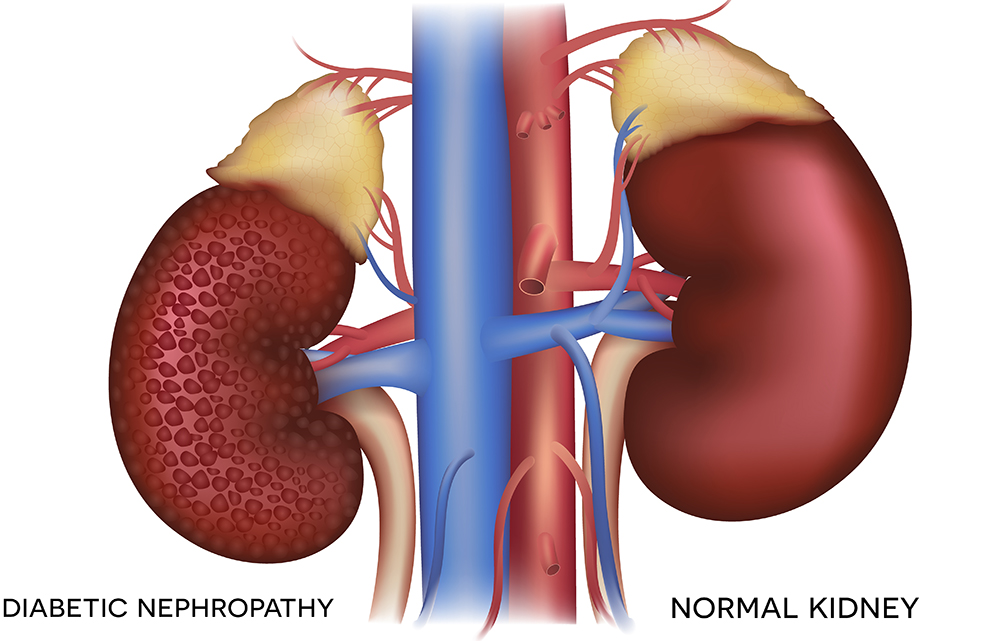

Typically, normal kidneys are about the size of a closed fist. However, in the case of polycystic kidneys, cysts develop within the kidneys, filled with fluid. Depending on their size and number, these cysts can significantly alter the kidneys’ size. Some medical records even depict polycystic kidneys that are as large as footballs and weigh over 20 pounds.

Apart from changing the kidney’s size, these cysts can disrupt healthy kidney functions and, over time, lead to kidney failure. Approximately half of individuals diagnosed with polycystic kidney disease will progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), necessitating either dialysis or a kidney transplant.

PKD is generally believed to affect both men and women of all ethnicities equally. However, some studies suggest a slightly higher prevalence in white individuals compared to African Americans and a slightly higher occurrence in females than males.

PKD ranks as the fourth leading cause of kidney failure in the United States, with an estimated 600,000 individuals currently affected by it.

Polycystic kidney disease is not contagious and cannot be acquired from a virus or exposure to someone with the condition. It is an inherited genetic disorder with two distinct forms passed down from parents:

ADPKD accounts for 90% of all PKD cases and is the most common inherited form. It is termed “dominant” because an individual must inherit one copy of the dominant gene from a parent to develop the disease. Symptoms of ADPKD typically do not manifest until individuals reach their thirties or forties.

Initial diagnosis of ADPKD often occurs when a doctor becomes aware of a family history of the condition or when symptoms or unrelated medical tests reveal kidney disease. Since ADPKD tends to run in families, individuals should inform their doctors of their family’s history with the disease. Despite shared genetics, the symptoms and impact of ADPKD can vary widely among family members, with some experiencing severe symptoms while others remain asymptomatic.

Common ADPKD symptoms include high blood pressure, blood in the urine, and pain in the back, sides, and abdomen. Roughly 60-70% of ADPKD patients develop high blood pressure, largely due to enlarged cysts exerting pressure on blood vessels within the kidneys. Management of blood pressure through medication, diet, exercise, and lifestyle changes can help control symptoms and slow the progression of ADPKD. Nephrologists can provide guidance on preserving kidney health as long as possible.

Additionally, approximately half of ADPKD patients may experience hematuria (blood in the urine). When urine appears pink, red, or brown, it signals the presence of blood. Typically, patients are advised to rest and consume ample fluids, along with acetaminophen (Tylenol®) for pain relief. Hospitalization may be necessary if blood persists after a couple of days.

Pain is a common issue in ADPKD patients, usually arising when kidney cysts become significantly enlarged. Pain may vary from mild to severe and can be intermittent or constant. Tylenol® can provide some relief, and surgery to reduce cyst size may be an option, although it is temporary and not curative.

Individuals with ADPKD have a higher susceptibility to urinary tract infections, which should be treated with antibiotics promptly to prevent the infection from spreading to kidney cysts. Since antibiotics cannot penetrate cysts, immediate treatment is essential.

Kidney stones are also more prevalent in ADPKD patients, occurring in 20-30% of cases—twice the rate observed in individuals without PKD. Passing kidney stones can be extremely painful and may result in visible blood in the urine.

As individuals with ADPKD age, up to 70% may develop liver cysts, although these do not impact liver function. Liver cysts affect men and women equally, with women experiencing them at a younger age and more frequently if they have been pregnant. Women also tend to have larger and more numerous cysts.

ADPKD can also affect the heart, with 26% of patients developing mitral valve prolapse (MVP), compared to only 2-3% of the general population. MVP can lead to palpitations, chest pain, and irregular heartbeats due to improper valve closure.

Headaches may result from high blood pressure or enlarged blood vessels (aneurysms) in the brain, making it important for ADPKD patients to consult a doctor about headaches, especially before taking over-the-counter pain medication. In cases of family history involving ruptured brain aneurysms, a complication of ADPKD, regular aneurysm checks may be recommended.

Many ADPKD patients remain asymptomatic, and routine checkups may not reveal any signs of the disease. Ultrasonography is the most common initial diagnostic tool for detecting ADPKD. Sound waves pass harmlessly through the kidneys and produce an image for examination. Enlarged cysts are visible if they reach a sufficient size.

Computed tomography (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also aid in diagnosis. CT scans use X-ray radiation and may involve contrast dye for improved visualization.

ARPKD is also a hereditary form of PKD but is associated with a different gene than the autosomal dominant variety. ARPKD is described as “recessive” because both parents must pass on a copy of the ARPKD gene for their child to develop the disease, even if the parents themselves do not have PKD. If both parents carry the abnormal gene, their child has a one in four chance of inheriting ARPKD. If only one parent

carries the gene, the child cannot develop the disease.

ARPKD affects approximately one in 10,000 individuals in the United States and tends to present symptoms early in life. An ultrasound can reveal kidney cysts in a fetus while still in the womb. Ultrasound imaging is safe and has no side effects, even for pregnant women and fetuses.

ARPKD can lead to severe complications, with a high mortality rate in infants, particularly within the first month of life. Survival depends on the severity of ARPKD, with roughly 50% of affected babies dying at birth or shortly after due to enlarged kidneys obstructing breathing. Some infants survive for days, months, or even several years, and rare cases involve individuals with ARPKD reaching adulthood. However, the disease also affects other organs such as the liver, spleen, and pancreas, resulting in issues like low blood cell counts, varicose veins, and hemorrhoids.

Children with ARPKD frequently develop high blood pressure by the age of one. Other complications may include frequent urination, urinary tract infections, and growth limitations due to kidneys’ inability to provide proper nutrients for bone growth.

To optimize the health of children with ARPKD, consultation with a pediatric nephrologist (a specialist in pediatric kidney diseases) is crucial. These specialists can prescribe medications to manage high blood pressure, administer antibiotics for urinary tract infections, and monitor kidney and overall growth. In cases of poor growth, growth hormones may be recommended.

By the age of 60, about half of ADPKD patients will require either dialysis or a kidney transplant due to kidney failure. For children with ARPKD, approximately one-third may need dialysis or a kidney transplant by the time they reach ten years of age.

Kidney failure manifests with various symptoms, including a general feeling of unwellness, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, difficulty breathing, weight loss, concentration difficulties, and depression. Dialysis helps remove excess fluids and toxins from the blood, with options such as hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis available.

A kidney transplant involves replacing non-functioning kidneys with a healthy one from a donor. To prevent rejection, anti-rejection medications are necessary to ensure the body accepts the new kidney.

In the year 2000, researchers discovered that a cancer treatment drug inhibited cyst formation in mice with the PKD gene. In 2003, another compound was found to prevent cyst formation in mice carrying the ADPKD and ARPKD genes. By identifying the processes triggering kidney cyst formation and experimenting with drugs to inhibit or block these processes, there is hope for advancements in PKD treatment and ultimately a cure.

North Las Vegas

4107 w. Cheyenne Ave.

No. Las Vegas, NV 89032

| Phone: | (702) 383-9741 |

| Fax: | (702) 387-1145 |

| Mon | 8:00 AM – 4:00 PM |

| Tue | 8:00 AM – 4:00 PM |

| Wed | 8:00 AM – 4:00 PM |

| Thu | 8:00 AM – 4:00 PM |

| Fri | 8:00 AM – 4:00 PM |

| Sat | 8:00 AM – 2:00 PM |

| Sunday | Closed |

Dr. Rafael Franjul Diaz graduated from Universidad Nacional Pedro Henriquez Ureña, Santo Domingo; the Dominican Republic in 2005 and worked as a primary care physician for several years. Completed his Internal Medicine residency at Nassau University Medical Center in East Meadow NY in 2015 with board certification in Internal Medicine that same year. Went on to pursue his dream of becoming a Nephrologist and was accepted in the Nephrology fellowship program at Newark NJ and will be board eligible for Nephrology Board Certification in 2017. His interest is in all areas of nephrology with special attention in glomerular disease and peritoneal dialysis with publication in this area. Above all, Dr. Franjul Diaz is a dedicated physician that works hand to hand with his patients and guide them through the course of their condition. In addition, Dr. Franjul Diaz enjoys walking and jogging and is proud to call Las Vegas his home.

Dr. Charissa Marie R. Carag obtained her medical degree from the University of the Philippines College of Medicine in 2011. In addition, Dr. Carag completed her Residency in Internal Medicine and Fellowship in Nephrology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, Illinois. Dr. Carag earned her board certification in Internal Medicine in 2016 and Nephrology in 2018. She is a hard working, competent, and compassionate physician focused on providing high-quality care to patients. Above all, Dr. Carag is married and in her spare time enjoys hiking and exploring the Las Vegas food scene.

Dr. Cyril Ovuworie also known as “Dr. Over-worry”, graduated from the University of Lagos School of Medicine, Nigeria in 1991. He further completed his Internal Medicine Residency at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York, 1997. In 1999, he completed his Renal Fellowship at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland. And then he moved on to do a Transplant Nephrology Fellowship at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts which he completed in 2000. He subsequently served as Clinical Instructor at University of California Los Angeles School of Medicine. Also Dr. Ovuworie participated in various research projects especially in the area of Endothelial Function, Homocysteine and Heart Disease. He and his colleagues have published many of their findings. most importantly, Dr. Ovuworie is on staff at most of the Las Vegas hospitals.